WILL BE UPDATED FREQUENTLY

WILL BE UPDATED FREQUENTLY

By Bill Hirschman

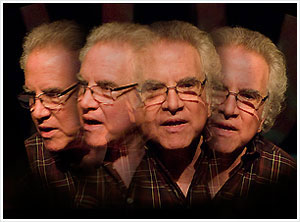

Joseph Adler, a titan who helped transform South Florida’s mainstream cultural landscape by mounting unblinking, dynamic work and by aggressively championing local artists, died Thursday morning of cancer at the age of 79.

Passionate and outspoken, curmudgeonly and supportive, gruff and loving, but unassailably a skilled artist, Adler had been a force of nature as producing artistic director of GableStage in Coral Gables since late 1998.

Other local artistic directors and producers did serious work before Adler’s ascendancy, but few if any pursued it with his single-minded commitment and devotion. He made such work his consistent hallmark and built a niche for patrons seeking challenging, thought-provoking theater with controversial themes — many mounted often only a season after leaving New York.

Challenging was a key word. Actor Nick Duckart, who was in two shows, wrote: “He wasn’t afraid to make his audiences uncomfortable. He welcomed controversy. He welcomed debate. Because he wanted to inspire, and inspiration doesn’t come easy.”

But his driving passion was as “an advocate for Miami artists in the Miami theater profession,” said Michael Spring, a close friend and director of the Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs. “Joe was outspoken about a lot of things, but never more than his deep belief that the talent was here to make a great theater community and he put his practice where his belief was. He hired those people and he made great theater using Miami talent. And that’s Joe’s legacy.”

Always concerned with the future of his art in the region, one of the last things he did in the past few days when he knew he was dying was to elicit pledges from GableStage Board Chair Steven Weinger, and Spring, who worked with him in the pending campaign to reopen the Coconut Grove Playhouse.

Spring said, “Joe called me earlier this week and he gave me very strong instructions. He said to me, ‘Michael, you and Steve are going to make sure that everything works out right.’ You know, there was no two ways about it. So Joe gave us our marching orders.”

He meant not just to ensure the future of GableStage itself but the effort by the theater, Florida International University (FIU) and the county to reopen the Coconut Grove Playhouse with GableStage as its managing company.

Adler had been noticeably ill for a year and a half, losing a great deal of weight. But he seemed to have recovered somewhat, continuing to give his pre-show curtain speeches live on opening nights until Watson in late November when his speech was pre-recorded.

As a result, friends said, his death was not unexpected, but still a surprise to those citing his indomitable character.

Actor Gregg Weiner had a particularly simpatico bond forged in 17 shows at GableStage ranging from Red to The Whale. “I knew he was struggling, but he was a tank. If anyone could fight through and win, it would be Joe. He’d been through such a full life up to this point and triumphed many times.”

A slightly restrained Adler was directing rehearsals of Arthur Miller’s The Price last month when the coronavirus closed all theaters. In January, he had rearranged the order of shows in the season so that The Price would open earlier than originally slated. He said in a February interview before beginning rehearsals that this would be his last directing assignment for the season; he had farmed out the other three plays to other directors.

He said that he had been planning for quite some time to scale back his directing duties and that he was currently in a long-delayed process to find someone to be a second-in-command and eventual successor. That would be a key to the company occupying the famed Playhouse, which has been closed nearly 14 years. A pending lawsuit blocking the effort was slated to have a key hearing just before the court system shuttered.

What most ticket-buyers did not know about was his unstinting nurturing support of the professional theater community. Unlike many artistic directors, Adler attended scores and scores of other companies’ productions, often volunteering his bracingly candid assessment.

Actress Erin Joy Schmidt wrote, “The truly remarkable thing about Joe was how much theatre he saw and when he was in the house you always knew it. You would get a phone call after the show, and sometimes it was good and sometimes it was bad, but you always knew how Joe felt.”

Further, he donated his stage to dozens of colleagues for staged readings of works in progress and he even loaned it for full productions to fledgling and struggling companies like Ground Up and Rising. He was unstinting in giving advice when it was sought by companies whom he considered colleagues not competitors.

“He believed deeply in the richness of the South Florida theater community,” wrote Antonio Amadeo, co-founder of the late Naked Stage company. “He thought the talent there was as strong as anywhere in the country and was committed to nurturing it.”

“When (we) wanted to do the first 24-Hour Theatre Project as a fundraiser to fuel the beginning of the Naked Stage, we asked Joe if he would be willing to help. Without hesitation, he enthusiastically opened up Gablestage and offered to carry the weight of the promotion, box office and space management. The decade of success that Naked Stage had and the impact of the 24-Hour Theatre Project could never have happened without his generosity and unwavering support.”

As a director, Adler could be quite insistently specific in what he wanted in performances to fit his clear vision of a piece, to the aggravation of some colleagues, especially newcomers. Admiring actors still tell stories about their arguments with him. But he also had an almost psychic relationship with experienced people he trusted like Weiner after working with them through the years, people whose pushback he respected and whose collaboration he valued.

His relationship with his artists went beyond a simple boss-employee situation. He tracked births and deaths in their families. Several actors recalled how understanding and supportive he was when they were going through a difficult time mid-show such as when Karen Stephens’ grandmother died.

Weiner said, “He officiated my wedding. He advised me during some of the most crucial times in my life. When I say he was like a second father, it’s not hyperbole. It’s because he was. That’s how I would introduce him. He was just so incredibly generous with me. His love, sense of humor, honesty, and passion are all in my heart now.”

Over the years, Adler took on a wide range of genres from Shaw to cutting-edge material. In the latter, he mowed down previous boundaries in Florida theater with a memorable production of Sarah Kane’s apocalyptic Blasted replete with blood, nudity and the destruction of the set each night. His strengths lay in examining race relations, sex, politics, interpersonal relationships and hot button issues in plays like The Royale, Constellations, Terrence McNally’s Mothers and Sons, the visceral Lieutenant of Inishman and Popcorn. While he could direct comedy, they were not his most memorable works. He even tried musicals, albeit off-beat ones like James Joyce’s The Dead and The Adding Machine.

He gave playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney his first chance to direct his own work professionally with The Brothers Size in 2011. More important, it was the first time a professional South Florida company had produced a full-length work by the MacArthur-winning Miami-raised playwright. Later, he hosted McCraney’s Choir Boy.

Under his leadership, GableStage brought tens of thousands of students in to the theater to see productions and exported special programs into the schools themselves including tours of Shakespeare.

Adler had been active locally before taking the reins of the Florida Shakespeare Theatre when it moved into the historic Biltmore Hotel and changed its name to GableStage to de-emphasize a reliance on the classics. He had worked freelance at the Coconut Grove Playhouse where he won a Carbonell for directing The Shadow Box, New Theatre, Area Stage, Hollywood Boulevard Theatre, Players Theatre, Ruth Foreman Theatre, City Theatre, Hollywood Playhouse and Shores Performing Arts.

Additionally, he had spent years producing and directing industrial films and commercials, recognized with the industry’s Clio Award. He also directed and or wrote independent feature films with titles like Revenge Is My Destiny, Scream Baby Scream and Sex and the College Girl.

His theatrical skill drew national attention. His willingness, even eagerness, to take on work that had barely closed in New York led play licensing companies like Samuel French to seek him out and offer him plays that other companies wished they could present first—or plays so challenging that they thought they fit his special skill set.

But he often knew about them already. He regularly went to New York City to scout out possible productions and often spent time at the Theater on Film and Tape department at the New York Public Library studying video of past productions.

Still, he sometimes stepped into unsought controversy. He occasionally would take artistic license tweaking a script much as some companies do with classic works, but with contemporary and living playwrights. In one case, Ruined, he made significant cuts reducing the running time, which brought down the ire of the licensing company and the material was restored.

Like any theater artist who took chances, some works were triumphs, some were not as successful. He joined forces with the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Public Theatre to co-produce an international three-city Antony & Cleopatra that did not land well.

His own life was worthy of a drama including decades of substance abuse and the death of a beloved wife before he finally reached a separate peace.

Joseph Adler was born in October 5, 1940 in Brooklyn. His family moved to Miami Beach to open a restaurant when he was a child. There, he developed an early interest in theater and spoke of being present at the Coconut Grove Playhouse on the fabled night in 1956 when Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot received its controversial American debut.

He left to study drama at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, but a summer course pointed him to New York University’s film program from which he graduated. He further developed those cinematic skills working as an account executive for the New York advertising firm Doyle Dane Bernbach.

Adler always was open about how during that time he developed a driving taste for cocaine, marijuana and alcohol that blighted his life deep into his career. His lifeline was his marriage in 1968 to actress Joan Murphy. She helped get him sober, but she died in 1995 as she waited for a double-lung transplant.

Returning to Miami to make an independent film, he stayed to create commercials, films as well as features for the cable business. The turning point came when he hooked up with a new theater troupe, Players Theatre and began a freelance directing career.

His list of honors was considerable including the Carbonell Awards’ highest recognition, the George Abbot Award in 2000; Champion of the Arts from by the arts funding group, Citizens Interested in Arts in 2016; a Remy Award from the Theatre League of South Florida; a Silver Palm Award; named to the Dean’s Leadership Advisory Board at Florida International University’s College of Architecture and the Arts, and received the 2017 ACLU Lifetime Achievement Award. During his leadership GableStage received at least 64 Carbonell Awards and at least 227 nominations. Personally, he earned 28 Best Director nominations, and won 13 Carbonell Awards.

He dabbled with expressionist styles, but he was a master of a relatively naturalistic almost invisible approach, especially given the wide and shallow stage at the Biltmore Hotel where GableStage stood. One result was often having scenes in which two people sat at a table simply talking to each other. In other hands, that would be a guaranteed formula for a static boring interlude, but which he turned inside out – he invested these scenes with intensity and used the focus to depict deep warring emotions.

As a proud liberal-progressive, his pre-show speeches were famous for the frequent statement “Now, I’m not going to get political. I’m not supposed to get political,” and then giving a wry smile as he made a verbal side-swipe at some conservative or reactionary situation. Unreservedly socially conscious, his preview nights for many productions were a benefit for some social or charitable organization.

News of his death stunned former colleagues spread across the state and the country who shared story after story.

Wayne LeGette, recalled, “Joe was the champion of never letting actors who had worked for him audition for him. He’d just call you. Maybe you’d come to a callback. Maybe. Usually you just got hired or didn’t. And it was never personal. And he always paid above scale. He loved and respected actors. “

Paul Tei, founder of Mad Cat Theatre and frequent actor in GableStage shows, wrote, “We worked, loved, laughed and fought like family. He could lift my spirits and he could break my heart but I cherish my time spent with Joe and I’ll miss him always.”

Duckart recalled an audience talkback for the show Masked, an explosive Israeli play about three Palestinian brothers locked in a life-and-death struggle. One woman challenged the cast how the company could do a play like that. “She went on to threaten Joe by saying she would never come back to GableStage because this play crossed the line. Joe, without hesitation, protected the actors by telling this audience member, ‘If you have an issue with the show, talk to me. It’s not the actor’s fault. Talk to me. And if you don’t want to talk to me, there’s the door.’ He had our back. Joe always had our back.”

George Schiavone, an actor and the photographer of most of the GableStage shows, wrote that he has known Adler since the 1960s, “two boys from Brooklyn…. His ‘always a new mountain to climb’ attitude created a milieu of searching and an example of what an inspired mind can do.”

Schiavone was loving, yet clear-eyed about his friend: “We had many conversations where he had a very definite point of view and then he could be quite receptive to criticism or advice… It’s hard for me to go on without sounding too flattering so I will say I have seen him in conflict, I have seen him be wrong, I have seen him be stubborn and yet I have seen him apologize…. He provoked, he inspired, he angered, he loved, he preached, he joked, he commiserated, he argued and people sought him out. I always loved driving with him and schmoozing… We would always pass our exit. I shall miss him terribly. There is a tear in the fabric of my life where Joseph was taken away from us. “

In his February interview, Adler said he was aware that he needed to ensure GableStage’s future and he had been planning for a transition to ensure the company’s future indefinitely: “It’s all being handled and we have all the right people involved. There’s no question about our ability to go forward, our desire to go forward, and we will.”

Survivors include his son, Noah, from his first marriage, and longtime partner Donna Urban, whom he always praised in his pre-show curtain speeches. Urban said he did not want a formal service, but she will let people know about causes he might have wanted contributions made to. Some friends expect to host a memorial celebration when people can gather again.

(One of the best profiles written about Adler was Christine Dolen’s piece in the Miami Herald on Dec. 22, 2009. To read, go to the Broward Library site.)

Adler with the cast of Casa Valentina in 2015

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design