Marco Antonio Santiago and Isabelle McCalla lead the Sharks in the dance at the gym in Actors’ Playhouse’s West Side Story / Photos by George Schiavone

By Bill Hirschman

In Actors’ Playhouse’s stunning production of West Side Story, one moving and chilling moment sticks with you.

After the fatal rumble, Tony and Maria clasp each other as the only sane harbor in a bitterly divided madhouse of hatred and violence. They sing, “There’s a place for us, somewhere a place for us, peace and quiet and open air….”

Their dream takes physical form: The young men and women who have been irreconcilably warring for the past scenes appear in pastel clothing and dance slowly, gently to the musical prayer. Couples start out in their own ethnic groups, but effortlessly mix together.

In a brilliant coup de theatre, the company comes to the edge of the stage in a single line blended as fellow members of humanity. For the first time, the hostility, the cynicism, the wariness that dominated their faces is banished, replaced by a beatific expression of peace and harmony. And then it disintegrates as the hatred and hardness reestablish themselves, and the dream evaporates.

The dance is dictated in the script, but lining them where we can see those expressions was conceived by choreographer Ron Hutchins and executed by a dancing corps whose faces mirror their characters’ souls.

It’s indicative of another triumph for Actors’ Playhouse, which pulls out all the stops to mount its annual winter centerpiece production that dazzles the audience, such as last season’s Ragtime.

Artistic Director David Arisco hired then molded a troupe of actor-singer-dancers who deliver a vibrant evening remarkable for its prolonged sections of power and verve. West Side Story was never a gritty documentary but a highly stylized theatrical social commentary. But this spin on Romeo and Juliet was transformed with unusual frankness for musical theater in 1957 to reflect disaffected youth, fatally warring gangs, an eternal generation gap, a resistance to assimilation, crushing urban poverty and destructive ethnic prejudice. Other than the period clothing and street slang, all can be extrapolated into 2016. Composer Leonard Bernstein, bookwriter Arthur Laurents, fledgling lyricist Stephen Sondheim and director-choreographer Robbins were amazingly – and depressingly — prescient.

One adult says to a Jet after an attempted rape, “You make the world lousy,” to which the teen snaps blithely, “That’s the way we found it.”

Everything you see has Arisco’s brand on it, but equal credit is due musical director Eric Alsford and, above all, to Hutchins who work is outstanding.

Hutchins has quoted liberally from Jerome Robbins’ iconic vocabulary that the genius developed out of modern dance, ballet and musical theater tropes. Hutchins had to; fans of the film would have felt cheated without the visuals of street toughs with cold eyes venting their anger with explosive movement that is both spasmodic and graceful. But Hutchins’ own vision is melded throughout, and audiences must acknowledge that Hutchins has elicited razor-sharp physical performances out of this troupe.

We don’t know who to credit for this, but these dancers are undeniably actors as well. In addition to the leading actors playing Riff, Bernardo and Anita, who must be superlative dancers, every last ensemble member, no exceptions, use their bodies to further express what you can already see is written indelibly in their faces whether it is street-calcified cynicism, unbridled joy or emotional devastation.

To appreciate the acting under Arisco’s hand, note that the script may have edges, but it’s strictly musical theater fairyland with a half-dozen implausible constructs starting with the love at first sight between Tony and Maria, and later, Maria instantly forgiving Tony for killing her brother. These and other elements simply should not work.

But they do. We never question these implausibilities because of the persuasive, torn from the heart performances of Sarah Amengual as Maria, Tim Quartier as Tony, Theo Lencicki as Riff, Marco Antonio Santiago as Bernardo and Isabelle McCalla as Anita.

Amengual is a Miamian who, fresh out of the University of Miami, was the first replacement Maria in the Laurents’ 2009 Broadway revival. Many actresses err by playing Maria as some dewy naif, but Amengual makes Maria simply a decent pure young woman who has yet to be contaminated by the hatred around her. Amengual is confident enough in the nuances of the part to make this Maria, with a huge grin and apple cheeks, wryly playful and engulfed in ecstasy at being in love. It goes without saying that her liquid soprano would make Bernstein very happy.

Quartier, resembling a taller gentler vision of Breaking Bad’s Aaron Paul, melds a lyrical expressive tenor with the ability to make Tony’s optimism plausible. His heartfelt delivery of “Something’s Coming” and “Maria” seem like natural expressions of someone whose feelings cannot be contained. Those two numbers, in fact many of the numbers in the show, are sung out into the audience with the actors facing the auditorium. Yet, Quartier and his colleagues never seem like they are singing a big musical theater number presentationally to the audience. They are always lost in their own thoughts and present in their own world.

McCalla, who recently appeared in the Asolo Repertory’s production in Sarasota, explodes across the stage like the sensual spitfire Anita should be, and her dancing-singing in “America,” is electric. Lencicki exudes the sense of a natural leader and loyalty that Riff requires, and Santiago is sinuous and taunting as Bernardo, a part he played in London. All three exemplify the just-out-of-adolescence seething sexuality that suffuses the entire piece.

A shout out to the “adults” who rarely get appreciated. George Schiavone gives the best performance we’ve ever seen him deliver as Doc, the aging store proprietor whose soul aches at hatred and violence. Ken Clement was playing Santa Claus in the national tour of Elf a month or so ago. St. Nick is unrecognizable here as Lt. Shrank, the gravelly, burned out, morally-corrupted bigot who embodies everything the teens are rebelling against.

There are shortcomings. The production lacks the menace and danger inherent in a toxic world whose forces are arrayed against these unlikely lovers. It’s still musical theater.

The only real tension occurs twice: in the brilliant powerhouse “Quintet” illustrating the anticipatory dread of the inevitable fatal collision to come, and the pressure cooker of “Cool.” Conversely, the mutual antagonism and naked bigotry of the Jets and Sharks, born so far back that no one remembers its roots, is palpable.

Furthermore, much of the cast – and this has always been the case since 1957 – is five to ten years too old for their parts.

But those deficiencies evaporate when Hutchins’ dance troupe rips loose with the competitive “Dance at the Gym,” the raucous “America” or the Robbins street scenes in the opening number in which fingers snap, legs fly into the air, dresses swirl, and shirts with flapping tails are soaked with sweat.

Arisco moves everything cinematically and even though there are occasional blackouts to change settings, a musical underscoring keeps the evening from stopping dead.

Tim Bennett created the dusty tenement neighborhood whose walls swivel to reveal interiors like Doc’s drug store and swivel again to create the gymnasium. Eric Nelson’s lighting was evocative, although sometimes it was hard to see some characters. Ellis Tillman, the dean of local costume designers, garbed everyone perfectly including the Shark’s color-coordinated outfits for the dance in shades of purple.

The sound quality, often a weak point in Actors’ Playhouse’s troubled auditorium, was improved by the loan of additional equipment. Shaun Mitchell’s design ensured no could complain that they couldn’t hear and the clarity made everything comprehensible. But it was so loud that any attempt to produce the illusion of a natural sound coming from the stage was in vain.

Alsford massaged the score originally meant to be played by 28 pieces so that it fit pretty well into a pit of nine musicians including Alsford on keyboards, Martha Spangler on bass, Julie Jacobs, drums; Roy Fantel, percussion; Andrea Gilbert and Gary Gottfried on reeds, Jack Wengrosky on trumpet, Jason Pyle on trombone and Jill Sheer on violin. The band sounded full enough, although on opening night there were a few jarring notes that will likely get smoothed out.

Before you go, the rest of the company has earned a virtual standing ovation: starting with Lindsay Bell and Emily Tarallo, two of the best dancers in the region, and Brian Dirito, Drew Arisco, Robbie Smith, Brandon Matthew McClesky, Sarah Crane, Nikki Allred Boyd, Jose Luaces, Macia Mac George, Hugo E. Moreno, Brian Varela, Jimmy A. Arguello, Christie Prades, Jessica Brooke Sanford, Valentina Izarra, Marilyn Caserta, Michael Freshko, and special nods to Jacqueline Lopez as Anbodys and Karl Skyler Urban as Big Deal.

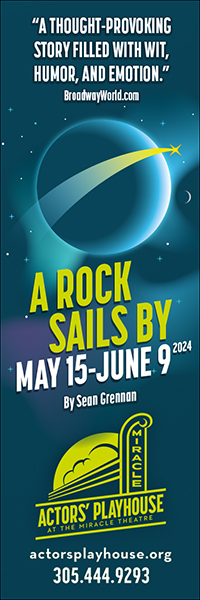

West Side Story plays through Feb. 21 at the Actors’ Playhouse at the Miracle Theatre, 280 Miracle Mile, Coral Gables. Performances 8 p.m. Wednesday-Saturday, 3 p.m. Sunday, 2 p.m. Wednesday Feb. 3. Running time 2 hours 35 minutes with one intermission. Tickets $59 Friday-Saturday, $52 other shows. The theater offers a 10 percent senior discount rate the day of performance and $15 student rush tickets 15 minutes prior to curtain with identification. Visit actorsplayhouse.org or call (305) 441-4181.

Sarah Amengual and Tim Quartier

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design