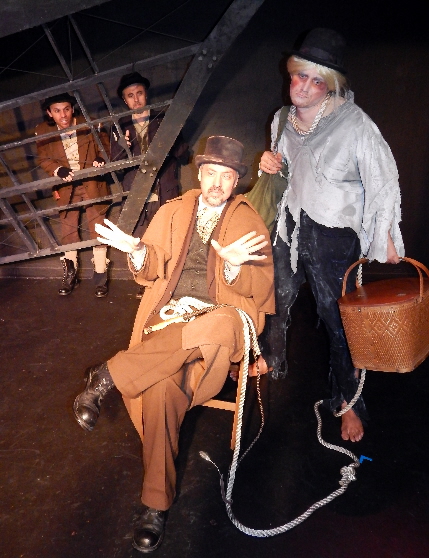

Lito Becerra and Seth Trucks eavesdrop on Skye Whitcomb and Christopher Mitchell in Evening Star Productions’ Waiting For Godot / Photos by Rosalie Grant

By Bill Hirschman

In Waiting For Godot, that classic of the Theater of the Absurd, nothing is more absurd than Man’s insistent search for some meaning in life. Nor more tragic, nor more comic, nor, in a strange way, more admirably if foolishly noble.

In Evening Star Productions’ courageous run at this Everest of a play, their response is broad comedy suffused into the intentionally pointless and protracted slog that is Samuel Beckett’s brilliant but unsettling manifesto of existentialism.

Fortunately, director Rosalie Grant and an indefatigable cast of clowns have a bottomless reservoir of comic tropes including more physical humor than a marathon of Keystone Cops films.

That welcome approach not only alleviates the pitch dark proceedings but is in itself a commentary on the laughable human pursuit of “sound and fury signifying nothing,” to quote an earlier playwright.

It should go without saying that Waiting For Godot, even when produced by the finest talents on the planet, has never been everyone’s cup of castor oil nor even that of a majority of discerning theatergoers. It demands not only that the performers work unusually hard, but the patrons as well. To be satisfied by the experience, you can’t just “give it a chance,” you have to buy an entire year’s worth of lottery tickets.

But honor that this tiny theater company in a Boca Raton strip shopping center has wrestled this work to the point that a willing audience will be intellectually stimulated. That may sound like a backhanded compliment, but given the innate difficulty and darkness of the material, it’s meant as praise,

If you were absent from literature class that day, Godot (this production prefers the pronunciation GOD-dough rather than Guh-DOUGH) tracks two days in the life of two impossibly woebegone hoboes: the philosophy-addicted Vladimir (Lito Becerra) and the bone-weary Estragon (Seth Trucks). They return daily to a post-apocalyptic landscape dominated by a bare tree. Plotwise, more happens on a season of Seinfeld.

They are loitering for the arrival of Godot, whom Beckett repeatedly insisted was not meant to be interpreted as God. Like any human beings in a close relationship, they banter, bicker, tell stories, embrace, fight, commiserate, chomp on vegetables, and consider hanging themselves. They spend a solid five minutes in tandem struggling to get shoes on Estragon’s feet.

Their musings are interrupted by the arrival of a snooty dapper gentleman Pozzo (Skye Whitcomb) who cruelly abuses his Golem-like hulk of a slave Lucky (Christopher Mitchell). Occasionally, a young emissary appears (Carsten Kjaerulff) relaying that Mr. Godot is not coming today, but assuring that he will be here tomorrow.

No matter how varied the conversation, no matter the bizarre appearances of Pozzo and Lucky, clearly all of this has happened over and over and over to these denizens, across at least a half-century and likely across millennia. The only comfort is their memory is so hazy that they cannot be sure they are stuck in this literary equivalent of Groundhog Day. And, of course, Godot never has and likely never will arrive.

The exchanges of dialogue can be banal or witty, and in very rare flashes, poignantly insightful such as observing of mortals “They give birth astride a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more.” Trucks, Whitcomb and Grant are experienced hands at Shakespeare, and the whole cast infuses a stilted, formalized over-the-top delivery that you can argue is intentionally artificial or, conversely, not quite a solid fit.

But no one can fault that vault of comic bits of business developed by Grant and, based on past performances, presumably from Trucks the sometime director, and Whitcomb, the artistic director of Outré Theatre Company. More than once, Trucks and Becerra get tangled in a Chinese puzzle made of flesh and bone. Or the tramps try on a newly-discovered hat to replace the ones they are already wearing, they trade off three bowlers in rotation in a vaudevillian bit that might have been choreographed by Charlie Chaplin.

With only three weeks’ rehearsal interrupted by illness, Rosalie Grant, assistant director Sara Grant and company have produced a well-oiled smooth delivery of the dialogue and what must be hundreds of bits of business.

Becerra and Trucks are blessed with rubbery mobile faces whose elastic mouths and bug-out eyes grimace from joy to fear to confusion to pain. Whitcomb’s harsh barked out orders to Lucky feel like being abraded with a rusty rasp.

Mitchell, under a wig of long white hair and sunken haunted eyes, stoically groans and pants in exhaustion much of the evening (plus a manic spastic dance that is frightening in its emotional release) – all the while succeeding at being pitiful as well as comic. But then Mitchell gets to create Lucky’s legendary flash flood of verbiage when the monosyllabic slave is ordered to “think” aloud. Slowly, through choked vocal cords not accustomed to being used, his Lucky begins to articulate some legitimate but esoteric philosophy of theology. Over several minutes, his voice picks up strength, volume and speed, just as the actual content descends into utter meaningless nonsense. It’s a superb moment.

The 1953 play written in French by an Irishman received its American debut at the Coconut Grove Playhouse in Miami in 1956 with Bert Lahr and Tom Ewell. Local audiences were baffled and one New York critic told his readers that he had no idea what he had just seen, but assured them it was great.

The work has been done over and over on Broadway, off-Broadway, colleges, small towns, major regional theaters. A memorable production was mounted by Robert Hooker’s Sol Theatre in 2004 in Fort Lauderdale with Jim Gibbons. The intellect-inspiring play has one other virtue for artists: the script is almost all dialogue with minimal stage directions or descriptions, and Beckett himself has only commented in succeeding years about the work. That means that theater artists are not encouraged but required to provide their own unique vision to flesh out the work.

Evening Star – an adult spinoff of Grant’s Sol Children’s Theatre – has used its creative reserves to bolster a modest budget. Ardean Landhuis and Kate McVay’s set overlays skeletal girders and shattered brick walls atop the traditional wasteland.

Christian Cooper dusts the soundscape with harsh winds and dripping water in the distance. Best of all are MJ Baum’s tattered filthy ill-fitting suits with fingerless gloves, battered bowlers and laceless shoes that would be rejected by Goodwill, but which imply that their owners have been repeating these routines for centuries.

Honestly, in 2017, this entire journey really does go on about ten minutes too long overall, even though the boredom of repetition is the point.

Indeed, more than 60 years after Beckett set out what still seems like an edgy, boundary-shoving work, Godot remains a challenge for both patrons and performers. But Evening Star’s edition makes it worthwhile for those on both sides of the footlights.

Waiting For Godot from Evening Star Productions at the Sol Theatre, 3333 N. Federal Highway, Boca Raton, through May 7. Performances at 8 p.m. Thursday, Friday, Saturday, 2 p.m. Sunday. Tickets $30 and $20 for students. (561) 447-8829. www.eveningstarproductions.org. Running time is 2 hours 35 minutes including half-hour intermission.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design