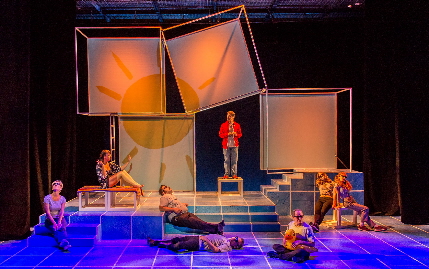

A trip to the seashore in Zoetic Stage’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time / Photos by Justin Namon

By Bill Hirschman

Usually, Zoetic Stage’s supremely skilled director Stuart Meltzer’s deft work is almost invisible to most audience members other than bringing a fresh vision to familiar titles. But his masterful work in The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time is so clearly displayed that his reinvention of the piece becomes the “star” of the production.

Forbidden to use any of the stunning aspects of the original award-winning British and Broadway transfer productions, Meltzer leads an A-game cast, designer corps, stage manager and other colleagues to deliver a fully original vision.

In his and their hands, Curious becomes a dizzying and accomplished tour de force of stylistic theatricality whose endless fluidity is a perfect metaphor for the whirling uncontrolled environment perceived by the hero, an autistic 15-year-old.

On an evocative but simple tiered-set, they arrange and rearrange anonymous skeletal blocks in a hundred combinations to stand in for a train, a bed or anything else, supplemented by slide-on stand-alone doors. A half-dozen actors in neutral costumes provide a chorus of onstage observers, slipping briefly into a half-dozen supporting roles differentiated solely by a clothing accessory and their acting skill. Like deus ex machinas, they hand off props to the lead actors with a practiced smoothness. It all resembles the kind of advanced director’s project used to earn a master’s degree in college.

But Meltzer is no novice aspirant, but one of the finest directors in the state. Melded with literally a thousand lighting, projection, animation and sound cues, the result is stunning recreation of an uncontrolled overwhelming environment as the hero sees it. The intricate and complex interactions of all those elements pose hundreds of opportunities for actors to misplace a box other than where a performer expects to sit down or out of a narrow square of light. The endeavor resembles those sliding plastic squares in a Chinese puzzle. Crucial to this intricately plotted dance, as it was on Broadway, is movement director Jeni Hacker working alongside Meltzer.

Set in a provincial working class English suburb, the tale starts off as a mystery with Christopher Boone, a math genius, trying to determine who gruesomely murdered a neighborhood dog. But his investigation forbidden by his single father and the desire to find his missing mother then send him into the wilds of urban London.

He struggles to keep the world in black-and-white order because he unable to filter out any input; it’s perpetual sensory overload. His world is slowly coming unglued because of the murder and emerging family secrets — finding people he desperately needed to trust have lied to him. So the wave flows from a precariously fragile order to growing unease to chaos to ultimate chaos. But as he manages to negotiate these waters, he discovers a minimal control, minimal accommodations and coping mechanisms until there is a new stasis and the optimistic hope for an independent future in the outside world.

Christopher’s tale is like a modern-day trip down the rabbit hole. Things that are familiar like the subway are a terrifying experience; the subtle sophisticated nuances of relations between men and women are opaquely indecipherable.

Like the 2003 best-selling novel by Mark Haddon, the play by Simon Stephens tells the story from inside Christopher’s mind. We see what he sees, hear what he hears. The playwright often presents people and situations that Christopher cannot comprehend or is misinterpreting which we in the audience perfectly understand, underscoring the tragic disconnect between Christopher and the world around him. His literal comprehension of people and conversational tropes produces some humor. At one point, a neighbor says to him at her doorstep, “I don’t think I want to see you right now.” He turns his heads 90 degrees and holds up a notebook to cover the side of his face.

The entire story is being read to by his teacher from a notebook that Christopher has written. While most of his prose is rightly straightforward, occasionally Stephens gifts him with forays into lyric verbiage such as describing his wonder inspired by seeing the starfield above.

To be fair, the script is not perfect. The journey and inquiry are not enthralling in themselves; the intriguing facet is that everything is told from Christopher’s viewpoint. As a result, script runs too long because Christopher’s usually passive behavior cannot sustain the entire running time. Even the fascination with the vibrant staging can only hold the audience’s interest for so long.

And finally, even having seen this twice before, I still can’t tell you what the themes are. It might be a reflection of everyone’s angst at feeling lost, helpless, adrift in this hyper-busy rushing world. But its worth really is in witnessing Christopher’s odyssey as pieces of his life spin apart and later reassemble into a more manageable world.

While in keeping with the consciously theatricality of the production, Stephens has the actors break the fourth wall, a debatable Brechtian choice because that distances the audience. Only at the very end of the play are we told that Christopher had earlier agreed to have his story retold in a play.

Which takes nothing away from Ryan Didato’s Herculean performance as Christopher. It is a difficult bi-polar challenge that Didato conquers admirably, especially the physicality. Much of the time, his Christopher stands erect, occasionally hunching his shoulders as he fiddles with a Rubik’s cube or the strings of a hoodie. He walks in straight lines, making military style 90-degree turns as if following an invisible lines in the floor. But when someone tries to touch him, the stimuli gets too loud or when the world emotionally becomes too difficult, he drops to the floor, curls into a fetal positions, shakes and issues forth an agonized scream of anguish. Didato makes both those modes plausible.

He is well supported by Stephen G. Anthony as his loving but stressed out blue collar father struggling to raise this difficult offspring by himself; Gretchen Porro as the caring teacher, and Niki Fridh as his missing mother.

Praise is also due the chorus who inhabit a few dozen roles, do 95 percent of the rearranging of boxes, supply the props, deliver disembodied voices in Christopher’s mind, stand still as part of Meltzer’s tableaux and portray individualized members of the passing masses of humanity on the street. Their skill is no surprise: The ensemble is comprised of veterans Margery Lowe, Michael McKeever, Zack Myers, Seth Trucks, Barbara Sloan and newcomer Rachel O’Hara.

Zoetic has once again assembled the work of an amazing set of designers and crew including Michael McClain’s set which features huge skeletal squares at the back with one tilted askew to indicate disintegrating order, the kaleidoscopic lighting by Rebecca Montero who is simply one of the best in Florida at what she does, Marina Pareja’s costumes with supervisor Debbie Richardson, Matt Corey’s complex sound design including unearthly musical interludes during scene changes, Natalie Tavares’ props, Greg Duffy’s animations, Steve Covey’s projections, along with technical director B.J. Duncan and dialect coach Rebecca Covey. A special nod is due resident stage manager Amy Rauchwerger and assistant Isabella Lisboa who nightly oversee this madness.

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time from Zoetic Stage as part of the Theater Up Close series performs through Feb. 3 in the Carnival Studio Theater at the Arsht Center’s Ziff Ballet Opera House, 1300 Biscayne Boulevard, Miami. Performances are at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday-Saturday, 3 p.m. Sunday. Tickets are $50-$65. Running time is 2 hours 30 minutes with one intermission. (305) 949-6722 or www.arshtcenter.org.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design