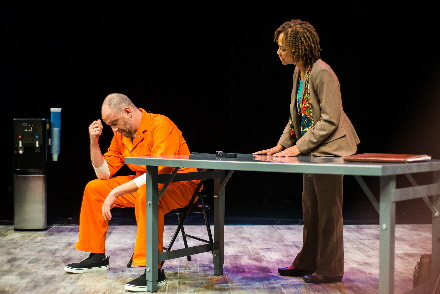

Karen Stephens questions Gregg Weiner in City Theatre’s Building The Wall / Photos by Justin Namon

By John Thomason

City Theatre’s production of Building the Wall opens with audio of then-candidate Donald Trump spewing some of his more incendiary anti-immigration rhetoric. The first line has yet to be spoken, and already you can feel your blood pressure start to rise.

But this is, mercifully, not a dramatization of Trump himself or his scorched-earth march to the White House; you’d need an absurdist playwright to re-create that. Written mostly prior to November 2016, Robert Schenkkan’s adroit cautionary tale about the harrowing endgame of Trumpism is a strange brew. A different beast from the studied historicism of Schenkkan’s All the Way, Building the Wall is a dexterous mix of reasoned political analysis and apocalyptic agitprop, where nuance and hyperbole commingle. Some theatergoers will hate the direction it takes in its final third—not all of them Trump partisans—but its urgency is enough to leave you shaken to your core.

It helps to have such flawless translators in the crack cast and crew of City Theatre. As The fourth and last company to produce this latest rewrite of the Rolling World Premiere through the National New Play Network, City Theatre has delivered the cerebral two-hander with expert, elliptical pacing, a frill-less presentation free of distractions, and a pair of actors whose complete immersion into their sparring cultural archetypes is never in question.

It’s set in an interview room in a Texas penitentiary two years into the Trump presidency. Gloria (Karen Stephens), a professor of history from an Ivy League university, has been granted exclusive media access to Rick (Gregg Weiner), an inmate sentenced for a heinous crime that Schenkkan unpeels in layers, like a rotten onion. Once the initial hostilities are dispensed and biases and motivations are assessed—Rick’s surprise and discomfort with Gloria’s race is palpable—Gloria launches her inquiry like any curious reporter should, by probing his backstory.

Hoping that sharing his side of the story will yield even a semblance of personal redemption, Rick unspools the narrative the led from his upbringing as a military brat with a father who attended the “church of Budweiser,” to his career in private-prison security, to his gradual embrace of candidate Donald Trump and involvement in his campaign apparatus. “I felt comfortable,” he says, recalling his first taste of Trump’s ravenous rallies. “I saw a lot of people who looked like me—ordinary people with families.”

Gloria hears the dog whistles: “White,” she clarifies. “And Christian.”

Rick is a microcosm for the millions of voters who gifted Trump with the presidency, concealing his bigotry and xenophobia behind seemingly apolitical bromides (“All politicians lie” is Rick’s familiar defense of Trump’s habitual mistruths) and a genuine, if naïve, belief that Trump’s populist rhetoric would reverse middle-class stagnation.

To Rick, Gloria epitomizes the cosmopolitan “elites,” always able to counter his defense of the president’s policies—especially the notorious travel ban—with inconvenient facts. Part of the pleasure, if that’s the right word, of watching Building the Wall is that we’re eavesdropping on a necessary cultural exchange. Most of us are siloed behind our trenches, rarely considering the viewpoint of the opposition, but Schenkkan plausibly imagines a civil dialogue.

With his shaved head, pitch-perfect Texan drawl and military comportment, Weiner’s embodiment of zealous nativism is stingingly accurate. At first glance, he could pass for one of the torch carriers in Charlottesville, but the Southern charm and occasional self-deprecation in Weiner’s delivery humanizes Rick. Stephens’ role seems easier on paper, because it’s not an ideological stretch for her to get into character: When Gloria blanches at Rick’s reverential mention of the disgraced sheriff Joe Arpaio, it’s easy to imagine Stephens reacting the same way.

The actors’ chemistry crackles, thanks in part to Margaret M. Ledford’s invisible direction. She stages this tête-à-tête on a mostly even emotional keel with occasional verbal flare-ups, like spikes on a heart monitor. She has Weiner and Stephens cycle through myriad positions on Jodi Dellaventura’s minimalist, utilitarian set of two metal tables, chair and water cooler, each player subtly shifting the power dynamic, if only for a moment. Grace notes, such as Stephens’ pointed movements of her audio recorder as a prodding mechanism, heighten the simmering tension.

By the time the mystery of Rick’s imprisonment has been revealed, the script has transitioned from recent history to a possible future, and the result is chilling—and, for some, alienating. At least six audience members walked out of Saturday night’s gala opening. The ones that stayed either audibly gasped or sat in horrified contemplation, painting mental pictures of the atrocities described onstage. I personally felt ashen and a bit nauseous; such is the impact of theatre at its most visceral.

Without spoiling much, Building the Wall concerns a slippery slope toward genocide whose parallels to Nazi Germany are all too apparent. Schenkkan must know that by evoking the Holocaust as a literary device, he will offend many. His dystopia feels wildly over the top even for an administration that shatters norms on a weekly basis.

But as a provocateur who wants to start a conversation, Schenkkan certainly succeeds. Plenty of great sci-fi stories have imagined unconscionable extremes to warn us about the pitfalls ahead—1984, Fahrenheit 451, Soylent Green—and Building the Wall feels cut from their cloth. Once it’s done leaving you speechless, it’ll get you talking.

One caveat about the production: Spectators enter the Carnival Studio Theatre by following either a blue or red line taped to the floor, directing them to the appropriate section of thrust seating. When the show ends, lighting designer Eric Nelson bathes each section in its designated color, reflecting the schisms between “red” and “blue” voters. But the unique coddling of racism and the arguable rise of fascism in the United States should have nothing to do with party affiliation. Many brave Republicans have rejected Trumpism. This isn’t about Democrat vs. Republican; it’s about democracy vs. authoritarianism. Reminding us of our traditional divides doesn’t help.

Building the Wall runs through Oct. 8 at the Adrienne Arsht Center, 1300 Biscyane Blvd., Miami. Show times are 7:30 p.m. Thursday to Saturday and 3 p.m. Sunday. Tickets cost $44. Running time is 80 minutes with no intermission, and City Theatre will present talkbacks following the performances Oct. 1, 6, 7 and 8. For tickets, call (305) 949-6722 or visit arshtcenter.org.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design