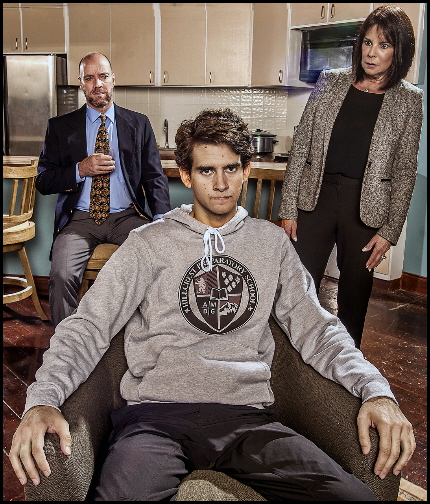

Joshua Hernandez has sent his parents Tom Wahl and Erika Scotti into a moral crisis in GableStage’s Admissions / Photo by George Schiavone

By Bill Hirschman

GableStage’s Admissions is one of the more uncomfortable evenings of theater that avowed liberals and proud progressives will sit through any time soon.

For while they see themselves as compassionate champions of social justice and equality – and see conservatives as unfeeling self-serving hypocrites – Admissions holds up an unsparing mirror that asks whether such advocates will stay true to their ideals when the consequences directly affect them and their families.

Playwright Joshua Harmon, who asked similarly tough questions in GableStage’s Bad Jews, isn’t targeting their sincerity so much as acknowledging human weakness when it’s your own ox being gored.

It’s the kind of assumption-questioning comedy-drama that Producing Artistic Director Joseph Adler loves; indeed, he started pursuing this work immediately after seeing its first preview in New York in February and GableStage may be the first regional theater to produce this wit-laced exercise in social commentary and wicked satire.

What Adler and his cast master so well is Harmon’s skillful whiplash of the audience’s allegiances, which are enlisted, then upended and then undercut. By the end, you’re not sure who you should have been rooting for and why.

The central character is Sherri Rosen-Mason (Erika Scotti), the admissions director of Hillcrest, “a second-tier, on-the-cusp-of-being-a-first-tier prep/boarding school in rural New Hampshire.” Sherri’s laudable crusade is to increase diversity in part by making the school seem more welcoming to minorities but also through affirmative action scholarships for cash-strapped applicants.

Her campaign is encouraged by her husband and the school’s headmaster Bill (Tom Wahl), who applauds Sherri’s achievement building a student body that was 6 percent minority and is now 18 percent.

Sherri repeatedly presses development department worker Roberta (Elizabeth Dimon) to insert more and more photos of minorities in the school’s recruiting catalogue. Roberta has no problem with frequent overhauls of the brochure, but she questions matter of factly why applicants are being wooed for their ethnicity rather than their intrinsic worth as individuals. She says that her repeated inability to see what Sherri wants may be based in “I don’t see color. Maybe that’s my problem. I’m not a race person. I don’t look at race.” The essential fairness of using that kind of yardstick is indicative of the philosophical conflict that Harmon is exploring. You appreciate Roberta’s view while applauding Sherri’s goal as the two concepts twist in on themselves over and over in their back and forth.

The snag occurs when Sherri’s son, the brilliant hard-working Charlie (Joshua Hernandez), is put on a waiting list for Yale while his life-long best friend, the equally privileged bi-racial Perry, gets in presumably because “he checked off a box” on his application. This sets Charlie off on a lengthy raging tirade decrying the inherent unfairness of white males being passed over because of gender and race rather than being judged on than ability and achievement. Is Kim Kardashian a minority because she’s half Armenian? He asks whether it was right for schools to discriminate for years against Jews like him when now they can discriminate because most Jews are white.

His blinding torrent of arguments persuasively punctures holes in the idea of affirmative action – an ideal that Sherri and many audience members whole-heartedly support.

Charlie rails about not becoming editor of the school paper because the advisor wanted the post to go to a less competent female student: “I am drowning over here, ok? … I get that there are entitled white men who assume they get a seat (at the table) without having to do anything to earn it; I do go to Hillcrest after all, and I do have eyes, but I’m actually one of the people working really f***ing hard to earn a seat, and every time I get close it’s like, ew! Not you! No one wants you here, f*** off.”

Harmon has Charlie’s brilliant mind race in a blinding speed that itself morphs into a very dark but very effective humor.

“And can someone please tell me, is Penelope Cruz a person of color, ‘cause she’s from Spain but she speaks Spanish, and so if she is of color then are we saying all people from Spain are of color? And if all people from Spain are of color, then why not French people, or Italian people? They’re all right there on the

Mediterranean. What is so special about Spain? Like, if Penelope Cruz is a person of color then I think we should discuss why Sophia Loren and Marion Cotillard are not. But if Penelope Cruz is not a person of color, then can someone tell me why a white lady with Spanish blood who lives in Spain is white; but a white lady with Spanish blood who lives in Argentina is not white. WHO DECIDES?”

Sherri is sympathetic but tries to defend the practice in terms any liberal would endorse and the balance scales begin to tip back. On the other hand, her husband, while liberal, has little patience for Charlie’s unrealistic expectations of the real world in which everybody uses connections and any edge they can to succeed. He accuses Charlie of being “a spoiled brat” who seems to want “a parade for doing his homework.”

To avoid spoiling the second half of the play, let’s simply say that Charlie has a change of heart in the name of idealism and altruism that turns everything inside out. The theoretical suddenly becomes very much a concrete conundrum that the adults must weigh. Suddenly, hypocrisy seems a reasonable option for caring parents. At one point, Sherri says to Bill, “If you don’t have a school like Yale or Harvard on your resume, that actually puts a ceiling on what’s possible in your life.”

While the ideas bandied about are deadly serious, Harmon has written copious sharp, funny dialogue for the adults to volley back and forth, including Perry’s mother (Barbara Sloan).

All of the actors under Adler’s direction expertly navigate the maelstrom of ideas. But Scotti (recently Joanne in MNM’s Company) is indefatigable as the fulcrum of the controversy and credible even when she has to make Sherri’s faltering values seem convincing.

Hernandez, a recent FSU grad to watch in the coming years, creates a Cat 4 hurricane of anger and passion, especially in his initial diatribe. He almost succeeds in the tough assignment that Harmon saddles him with – his ideological U-turn and his sacrificial choice to put his money where his mouth is. Yes, 17-year-olds can be mercurial but Harmon makes this an acting challenge that is more dramaturgical than realistic, especially after Hernandez was so convincing in his protracted deep outrage earlier in the play.

Adler and company makes this 20th season ender yet another example of GableStage’s commitment to sending audiences out with plenty to argue about.

Admissions runs through Nov. 11 at GableStage, 1200 Anastasia Ave., Coral Gables, inside the Biltmore Hotel. Performances 8 p.m. Thursday-Saturday, 2 p.m. and 7 p.m. Sunday. Runs 1 hour 30 minutes with no intermission. Tickets are $52-$57. For tickets and more information, call 305-445-1119 or visit GableStage.org

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design