Mallory Newbrough and Robert Richards Jr. in Area Stage Company’s 2017 production of An Octoroon

Editor’s note: This story is guaranteed to anger somebody. It likely will anger nearly everyone, just for different reasons. The statements quoted may go too far for some, not far enough for others. Some are inarguable fact. Some are perceptions. None apply to every theater or artist in the community. But there is, we hope, in this very long story, the discovery of underlying truths that beg to be addressed. We strongly encourage you to react and respond in our comments section.

By Bill Hirschman

Everyone had a story, each told with mordant humor and banked anger.

Veteran Black actor and educator Keith C. Wade told of a publicity photo shoot when the play’s director said, “Hey, listen, kid, I can’t see your eyes.” Wade jokingly opened his eyes wide. The director responded, “No, no, you look like a spook.”

Shirley Richardson, co-founder of M Ensemble, Florida’s oldest continuing Black theater, remembers the white woman on a grant review board saying “it looks like you are looking for welfare.”

Actress-musical director Christina Alexander laughs recalling a production of Elton John’s Aida in which white actors played Black slaves singing “The Gods Love Nubia.”

The stories among the 21 artists of color and white artistic directors interviewed were endless. Each of the artists shared stories of racism infecting the Florida theater community, spotlighting specific problems and offering potential solutions.

Some cited random unintentional micro-aggressions in pressure-laden rehearsals, avoidable if people had simply thought about what they were saying and doing. Others underscored systemic failings whose reform will require leaders, supporters and audiences to prioritize revaluating everything from what goes on stage to who decides what goes on stage.

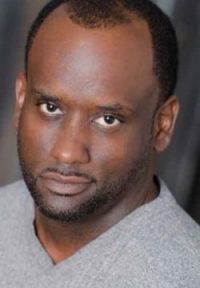

Keith C. Wade

“It’s talked about in dressing rooms, and for a lot of Black actors, we kind of laugh it off: ‘Oh, yeah, you had that experience, too,’ ” Keith Wade said. “There’s this go along to get along kind of mentality where we’ve become so numb to it that now you accept it, you swallow it and you keep on going because that’s the business. But the result is a simmering resentment, simmering anger.”

Still, “overt racism is not really what the conversation is about today” in South Florida, said Nicholas Richberg, a Cuban-American actor with multiple Carbonell Award nominations and currently serving as managing director of Miami New Drama. “The conversation is about lack of representation. Are there enough diverse voices within your organization so that it’s not just one person’s point of view that is deciding the aesthetic?”

The problem is visually inescapable with Richberg referencing Miami-Dade County’s majority minority populations. “We have a problem with the fact that we call ourselves the theater community and we don’t look anything like the community that we serve,” he said.

Failing to address the issues in the short term might not upset some current white audiences seeking a reinforcement of status quo, especially in Broward and Palm Beach Counties where they constitute a majority of theatergoers and the population as a whole. But several people warned that long term, not taking significant action could doom South Florida theater’s upward trajectory as a thriving arts genre with future audiences.

“That is really what’s going to separate companies that are going to be left behind from companies that are going to move into the future because this community, as well as America in general, is no longer white,” Richberg said.

It is safe to say that nearly all of the people who have committed their lives to running theaters in South Florida see themselves as progressive, socially-conscious people who have always opposed racism and can point to efforts to diversify their programming and casting. But their efforts are limited by their own background, critics contend.

“The major theatre companies in South Florida all have (older) white artistic directors, literary managers, and whether they mean to or not, they only look at theatre through their own narrow scope,” wrote Luis Roberto Herrera, a New World School of the Arts grad and a playwright now living in New York.

Therefore, troupes need to recruit diverse voices not just to the auditorium seats but to leadership positions in the companies, several interviewees said.

FIRST STEPS

“It’s not only about what’s presented on stage, but how the whole company runs.” — Margaret M. Ledford, artistic director of City Theatre in Miami.

While some artistic directors have long acknowledged they should expand their efforts, the eruption of outrage this month nationwide about theater’s shortcomings – an outgrowth of the broader social tumult – has forced many artistic directors to reexamine policies and practices.

Local companies’ immediate response were missives on social media pledging their renewed commitment; some acknowledged the possibility that they had unknowingly contributed to the problem — although few specified any perceived or actual sins.

Christina Alexander

Christina Alexander, who is also a consultant on racism in the arts, warned that “We need ‘#solutions,’ not statements; ‘#strategies,’ not sorry.” She calls for proactive steps, not simply ones reacting to being called out.

Some white artistic directors like Ledford and Matt Stabile of Theatre Lab in Boca Raton pledge to identify problems and act decisively, even though they have made efforts before this.

Ledford, whose Summer Shorts casts are a rainbow of ethnicities, has spent nights in deep introspection “trying to understand how I have been complicit in a larger system of privilege.” She hasn’t spoken much publically “because my voice right now doesn’t need to be heard until I know where I’m sitting. But a veil has been removed. Whether I willingly kept the veil there or just ignored it, that can’t happen anymore.”

Across the region, leaders like Stabile are attending or creating listening sessions, formal and informal, with artists of color from actors to designers to playwrights to prop managers.

“You don’t know what you don’t know,” said Stabile who frequently uses what he prefers to call color-conscious casting. “We’re hearing from performers of color that (they) are not valued in our spaces. And so unless you’re willing to sincerely listen and educate yourself on what is happening and value the personal perceptions and experiences of people who are living a vastly different existence than you are, then you’re not going to know what you have to do.”

Developing a bullet-by-bullet action plan is a priority, but they feel it needs to be done carefully. “I didn’t want to be in a position where our theater put out an accountability plan that either didn’t go far enough or that we couldn’t achieve. We are structuring our plan accordingly so that we can look back in three months, six months, a year, two years and say, yes, we are doing this,” Stabile said.

“I’m very proud of the (diversity development) work that we did this year. But frankly, it’s the tip of the iceberg,” Stabile said. For instance, while Theatre Lab has helped developed works-in-progress by playwrights of color, “I’m a little I’m ashamed that we have yet to produce a playwright of color. You’re not giving voice to those artists.”

Yet, morphing broad mindsets inculcated over decades and then infusing lasting reforms into the fabric of a company will take time, said James Randolph, an honored Black actor and educator in Miami for decades.

Richberg expanded, “You have to make the effort to foster an entire generation of those artists and critics and designers and administrators and patrons and donors. You don’t just snap your fingers or do one show and then say, ‘Well, nobody came’ or contact the Arts and Business Council and say, ‘Well, they couldn’t come up with any Black board members for me.’ It takes a real concerted dedication over the course of the life of our organizations to create that kind of change.”

DECISION MAKING

“When you’ve got essentially nothing but white Anglo people in decision-making positions, it’s hard for them to think outside the box” – Actress Karen Stephens

Much of the problem stymieing a season of “woke” work, workplace sensitivity and a year-round company commitment to changing the paradigm is the dearth of diverse voices in the decision making processes, from the board rooms to the company management to the office staff.

Simply, it is nearly impossible to satisfactorily make diverse-influenced decisions and policies – even to be aware a problem exists — when nearly everyone involved comes from the same Caucasian background.

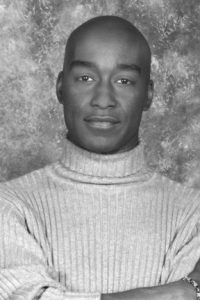

Nicholas Richberg

“It’s not by malice,” Richberg said. “But (white leaders) will produce shows that are about people like (them).… That’s not racism. But the problem becomes when you’re not aware (that you are using) your own preferences, your own biases, your own self.”

So, in an essay for the Howlround theater website, Kelvin Dinkins Jr. and Al Heartley prescribe “dismantling white supremacy culture means de-centering power, yielding power, and, in most circumstances, having the fortitude to step aside.”

That may be a problem here. South Florida regional theaters still are headed by their founders, understandably possessive after investing 20 or 30 years in these companies – and they are white or Hispanic. These are not venerable institutions with a history of successive leaderships. Indeed, one quiet criticism for several years, underscored by the recent passing of Producing Artistic Director Joseph Adler at GableStage, is that few companies other than Palm Beach Dramaworks, have created a clear succession plan.

The lack of diversity in some companies’ corps of decision-makers goes beyond artists; they include board members and linchpin donors. Anecdotally, local efforts have not been overwhelming to bring influential diverse voices into the room where it happens. With a few notable exceptions, they certainly have not been especially successful. Indeed, one of the priority items still on Adler’s to-do list when he died in April was to bring more racial diversity to his board before taking over the Coconut Grove Playhouse.

Some companies such as Theatre Lab, which is actually under the aegis of Florida Atlantic University, have pledged to add people of color to their boards and as they hire new or additional staff.

That may not be as tough a challenge as some expect, some observers said. An ample community of diverse citizens might be interested in such roles if they were made aware that their involvement was sought, said Kent Chambers-Wilson, an actor, playwright and past president of the South Florida Theatre League. They might be easier to enlist if they were not expected to be rainmakers and donors as is often a requirement. Also, board members of color could just as easily be experienced performers, retired artists or current teachers of theater.

CHOOSING FARE

“White mainstream theaters exist in a white mainstream country. So it doesn’t behoove them to think beyond their own parameters of existence. Some do. Maybe not enough.” – Karen Stephens.

The easiest and most high-profile step would be changing what has been chosen to appear on stages. No one interviewed believes past efforts to diversify what is seen on stages go far enough or deep enough. And some perceive existing efforts of some companies as a minimal dutiful sop to their social conscience or just fulfilling a line in a grant application.

But first, examine the existing baseline. Virtually every company in the region produces work with racial themes, some regularly like GableStage in Coral Gables whose seasons have included White Guy on the Bus, Ruined and The Royale.

Every single theater uses multi-ethnic casts at some point in their season. The practice is especially prevalent in musical ensembles and jukebox revues, but also occurs with artists of color in leading roles.

But many companies identify one slot in their annual schedule for “pushing the edge of the envelope” by producing shows with racial themes. Frequently, they occur during February’s national Black History celebration that Black director Teddy Harrell Jr. jokingly deemed “the holy month,” which lands deep in tourist season. Others schedule them before or after the white snowbirds’ visit.

In a different category are companies whose primary identity is producing diversity-focused work with diverse directors, playwrights and designers. They include M Ensemble; Arca Images guided by Pulitzer-winning playwright Nilo Cruz; Centro Cultural Espanol; the African Heritage Cultural Arts Center where Harrell is based; Juggerknot Theatre Company; Miami New Drama; the International Hispanic Theatre Festival; Little Havana’s Spanish-language Teatro Avante, and Main Street Players, which alternates Hispanic-themed work with more general fare. Notably, all of these are based in Miami-Dade County.

But even some of them weigh their season’s choices gingerly. Their race-conscious productions often hew to familiar titles and “approved” name playwrights like August Wilson, said acclaimed actor Ethan Henry, who played the leads in several Wilson plays here before leaving for Los Angeles.

“I love Raisin in the Sun but we’ve seen it,” said Chambers-Wilson, echoing a sentiment from other colleagues. “You rarely see a Haitian story or a Jamaican story.”

Yet potential fresh work from fresh voices abound. “I mean, those names are out there. If they were looked for, they could be found,” said Stephens, who has won acclaim for her work as African American characters and in race-neutral roles across the region.

Shirley Richardson

Even identity-centric theaters like M Ensemble sometimes are selective about uncomfortably challenging shows they schedule, especially when trying to attract a multi-ethnic audience, Shirley Richardson said, but she resents the stricture. “We shouldn’t have to be careful of how plays talk about black issues. But that’s what we have to be careful of, (being) offensive to whites.”

For instance, Amiri Baraka’s Dutchman and Stephen Adly Guirgis’ Jesus Hopped The A Train – which were produced locally years ago – are perceived as tough sells today. Many white, Latinx and African American theaters have usually “allowed their patrons to stay within their comfort zone and that comfort zone is a very small bubble,” Chambers-Wilson said. Ironically, lauded Miami native Tarell Alvin McCraney didn’t have a professional production of his imagistic work in his hometown until GableStage mounted The Brothers Size several years after he became nationally renowned.

In truth, invigorating challenging works are being done by some mainstream houses: Stuart McKeever, who is white, directed Zoetic Stage’s edition of Suzan Lori-Parks’ Topdog/Underdog and Christopher Demos-Brown’s American Son. John Rodaz, who is Hispanic, spearheaded Branden Jacobs-Jenkin’s An Octoroon at Area Stage Company.

But like a schizophrenic, theaters struggle with sating some audiences only interested in comforting mainstream fare and others hungry for thought-provoking and boundary-pushing work.

The problem with both paradigms is that even the most socially conscious white theater executives have a narrow exposure to other voices and they choose their season titles based on their own background and artistic preference, most interviewees agreed.

Karen Stephens

“The gate keepers in a racist society are people who are socialized by the racist society. They are not socialized to think beyond their own purview. So they don’t feel it behooves to provide access to people who are other than them on a consistent basis,” said Stephens.

She pressed, “It’s kind of like ‘We’ll put something in our program to say we’re artistically aware of social issues.’ But they don’t plan their seasons around it…. I don’t see that has been their priority in the past.”

In some cases locally, the relatively short rehearsal periods pressures white directors to choose plays they already understand with actors whom they already know can do the roles and plays which have a better chance of financial success with the audience, Chambers-Wilson said.

Some South Florida theaters are reticent to shove, let alone nudge, the boundaries because they have spent years developing a recognizable mission and developing a core audience of subscribers and donors drawn to that thematic/stylistic niche; their loyalists rebel when an offering ventures too far outside that tonal niche.

But Michel Hausmann, the outspoken artistic director and co-founder of Miami New Drama, classifies choosing primarily white-influenced stories as “a reflection of what white supremacy means.”

So the nagging question persists: Will theaters trying to stay fiscally alive during and after the pandemic, will they be able to follow through on their sincere intent to increase more inclusive, challenging and diverse fare if their core audience fails to renew?

That concern doesn’t begin to address the bedrock vision of attracting a multi-cultural audience, although every interviewee of all ethnicities believes that must be a significant goal.

Keith Wade and others counter that some artistic directors and boards underestimate African Americans’ appetite for thought-provoking work despite the stereotyped expectation that they are more likely to support light frothy comedy. “I compare it to like eating fast food. Like McDonald’s is good for a day, but you don’t want to continue eating that every day. Tyler Perry is okay for a laugh. But when you ignore work like August Wilson, you are doing yourself a disservice,” said Wade who is also a playwright.

They are not mutually exclusive, Chambers-Wilson said. “We as artists drive two missions: One, of course, is entertainment, but also we should give them a safe space to see a view of the world they would not normally participate in.”

Indeed, a variety of tones even in racially-themed plays is desirable. “I hope we don’t make the mistake of thinking that theater of Black pain is the only way to” address diversity in a season “because frankly, if you are living a traumatic experience, do you want to go see it reflected on your stage” all the time, Stabile asked.

Cary Brianna Hart

One solution is mounting a production that speaks to the universality of people even when it is rooted in one group’s experience, said Carey Brianna Hart, an actress, director, stage manager and sound designer. “You’re supposed to push that universal chord… that says that we are different, we are separate, but we also are the same in our struggles, although (we go) through these things at different times, and the weight of these things may be different on different people.”

Richberg added, “I’m a firm believer that you can tell a story in Miami that will appeal to Latin people and Black people and white people and Jewish people. They will all go to see the same show if you have your finger on the pulse of unity. It’s not about one or the other.”

CASTING

“I can see (having) a black Daddy Warbucks, but it ain’t gonna happen.” –- Kent Chambers-Wilson.

While no one believes there are enough opportunities for performers of color (for that matter for anyone in South Florida), the cold fact is that African American and Latinx performers can be found on nearly every stage in the region including those perceived as “mainstream white” companies.

The catch is what they are being cast as and when and how often and why.

Over and over, interviewees like Henry sardonically joked that opportunities for work suddenly peak for a company’s obligatory Black History Month play, then the demand for their services dissipates. “I would like leaders to know is that there are other times during this year that we can work,” Henry said dryly.

Whether that lack of opportunity exists or not, the perception is strong. It helps explain why many young artists of color leave the region, Richberg said.

Even when they are cast in an ensemble, the perception among some performers is that someone is “checking off a diversity box” for seeking foundation funds.

The unconscious default ethnicity on casting by white directors is very often white, said Stephens who recently played Winnie in Beckett’s Happy Days at Thinking Cap Theatre in Fort Lauderdale.

Elena Maria Garcia

That results in “exclusionary tactics that take place in this industry down here,” said Elena Maria Garcia, a three-time Carbonell-winning actress, playwright and educator. She cited as an example that when some theaters mount staged readings, it is rare to see an African American in the cast.

Black actors have a slight edge if the character is “angry,” but they aren’t considered as often for a sympathetic character, Chambers-Wilson said.

In South Florida where a good deal of the talent pool has Hispanic roots, Latinx performers have less of a problem getting cast in traditionally “white” roles, although some interviewees said it depends on their appearance and accent. But African American performers have a much tougher time getting cast in major race-neutral roles, artists reported.

More problematic is color-blind casting, seeing the character as race-neutral or to make a point about the universality of the character by casting against traditional tropes.

Sometimes it’s a defiant declaration: Black actress Sipiwe Moyo triumphed as the title king in New Theatre’s Henry V in 2011. The mainstream Maltz Jupiter Theatre, echoing the casting of the Broadway production, cast an African American woman as a white Nora’s daughter in A Doll’s House Part II last season. But interviewees said that’s rare here — a far cry from Great Britain where race is rarely a criterion in the casting discussion,

But not everyone is a fan of the practice. August Wilson repudiated it during a 1997 debate, arguing that the answer to a lack of black casting in mainstream white plays was to write more Black roles and produce those plays.

Wilson said at the time, “To mount an all-Black production of a Death of a Salesman or any other play conceived for white actors as an investigation of the human condition through the specifics of white culture is to deny us our humanity, our own history.”

Race and diversity were very conscious criteria when Stabile cast shows this past season for Theatre Lab. In The Glass Piano, a fantasy about a troubled royal family, only the befuddled authoritarian king was white. In its youth-oriented When She Had Wings, the role of a white young Nebraska girl who dreamed of emulating Amelia Earhart was given to an African American actress playing a Florida girl because it “was very important to me that these students of color saw a positive representation of their own experience reflected on that stage,” Stabile said.

Such color-conscious casting need not be a perfunctory nod to social conscience but an invigorating intellectual and emotional exercise for audiences of all ethnicities, gender and backgrounds, some said. Several interviewees suggested no-excuses productions of mainstream titles could produce new life, new audiences and new overtones even for core white audiences.

Carey Hart dreams of playing Blanche in A Streetcar Named Desire in which she might be a Haitian princess fallen from once wealthy agrarian family and who has now come to live with a sister married to a Jamaican man in a middle-class Black neighborhood. Ethan Henry suggested revitalizing mainstream classics with African American casts such as 12 Angry Men, Steel Magnolias and The Cherry Orchard. Keith Wade, who has played Othello, longs for a white actor in the part so that he can play Iago.

Another key stumbling block is auditions. Several South Florida artistic directors who have chosen a play with multiple parts for actors of color scramble to find skilled performers. There is a perception among many white directors that the talent pool is not very large, especially for middle-aged African American males.

One observer said not for attribution that, of course, sometimes a specific actor doesn’t get hired simply because he isn’t right for the part or is just not good enough.

Ron Hutchins

But interviewee after interviewee contended that the pool is adequately deep; it’s just that many performers of color simply don’t want to put themselves through the audition process – thereby creating a self-defining vicious cycle, said choreographer Ron Hutchins. Especially in Miami, a cadre exists of Latinx performers who have had lengthy careers working for Spanish-only companies.

Yet, Latinx performers told producer William Fernandez that they feel opportunities here are limited, “even fairly impossible,” other than for a small group of actors who are regularly hired. “They say when there are opportunities, no one really reaches out to them, so they have no way to know about this,” he said.

But even when they are aware of auditions, they perceive a can’t-win bias based on the titles chosen and the company’s all white leaders. Some believe they are not going to be welcome to audition, Fernandez said. Indeed, some audition announcements actually ask for “a white male, age 35,” Chambers-Wilson said.

Some ask why they should audition if there is no definable role for a person of color, said Carey Hart. She strongly advises colleagues to audition for everything if only to get themselves in directors’ consciousness for the future.

But instead, “they find a home where they feel safe like M Ensemble, and they tend to just only work there because it’s where they feel valued and comfortable and safe,” Stabile said.

Some people resist auditioning if they perceive the role to be the token diversity role, Harrell and Alexander said. She noted, “Black artists are still dealing with these animosities because (of the sense that) you’re kind of our resident Black girl.”

And in much work by white playwrights chosen for South Florida companies, the “minority” character has limited emotional depth like “the sidekick,” Chambers-Wilson said.

Obviously, the other half of the optimum paradigm puts the responsibility for extra effort on the artistic directors, Fernandez said.

When directors say, “We cast who comes to our open audition, that, to me, is a very lazy answer,” Richberg said. “If you actually want to make a change, you can’t just be passive about it. You actually have to go into the community. You have to seek people out. You have to make phone calls.”

That involves scouting trips to shows featuring artists of color. But other than GableStage’s Joseph Adler, most South Florida artistic directors — their schedules already jammed during the season – simply don’t go to many productions at any theater, let alone to see the array of talented performers such as those in the African Heritage Cultural Arts Center’s 2018 production of The Colored Museum.

Fernandez, who did much of the casting for the eight-month run of the immersive Amparo in Miami, said he had to do “a bit of digging” to keep the show staffed. But “they’re there.” he said. Artistic directors who say they can’t find artists of color “they didn’t make an effort to look for them. It’s easier to say they’re not here.”

Diversifying the fare and the casting are not enough, interviewees said. Theaters need to hire designers and especially directors of color who can bring their unique backgrounds to interpret these works, said Chambers-Wilson. The best white director cannot bring the most telling insights of a lifetime to the plays of Suzan-Lori Parks, Lydia R. Diamond or Dominque Morisseau.

AUDIENCE ISSUES

“It’s a very Field of Dreams kind of situation. If you build it, they absolutely will come because the route of getting to the heart of a Black theater is having Black people in it.” – Keith Wade.

Besides the artists and decision makers, the audience is other key factor. Can theaters keep their current audiences and attract new ones, especially patrons of color?

“Theaters and producers are always looking out for their bottom line and their patrons to see what’s going to bring in the dollars, right? So if they have a majority white subscriber base or patron base, they have to decide if those people are open to being challenged in an artistic way on social issues,” Stephens said.

Kent Chambers-Wilson

Some observers note that Miami-Dade has a far more diverse population that is theoretically more receptive to diverse fare than the crowds in Broward and Palm Beach counties. Kent Chambers-Wilson, a Carbonell judge who sees work throughout the three-county region, said he is often the only African American in the audience when he attends a show north of Boca Raton, although some observers wondered if many people of a working-class economic level cannot afford those tickets.

But others believe that artistic directors and their boards underestimate a large segment of their core audience. The older, wealthy white audiences raised in the tri-state area retired to Miami because, in part, the gritty urban vibe echoed where they came from, Chambers-Wilson said. Many of those theatergoers throughout the region grew up seeing calorie-empty entertainment on New York stages but also some of the most classic thought-provoking work of the century. To a degree, all they want is “a good story,” said Elena Maria Garcia.

Although multiple venue changes and other issues closed New Theatre in 2016, audiences flocked to the company for many years in Coral Gables “run by a Cuban man with an accent… that hired people of color, that commissioned writers of color, that produced a Pulitzer Prize-winning play from a writer of color,” recalled Richberg who worked there as a dresser in his youth.

“It’s amazing to me that 25 years later, it feels revolutionary to be saying that we’re hiring people of color at Miami New Drama and hiring actors with accents…. I don’t remember anyone really thinking about it as revolutionary. (Artistic Director Rafael deAcha) was just doing good work that looked like the city. But somehow we’ve gotten to a place where 25 years later, that’s a big, big idea.”

Progressive mainstream theaters have been trying to attract African American and Latinx audiences for years by programming Black or Hispanic themed works, for decades in the case of Actors Playhouse in Coral Gables, which has produced Nilo Cruz’s The Color of Desire, Havana Music Hall, Memphis, Carlos Lacamara’s Havana Bourgeois and an Evita in both English and Spanish.

Several leaders express frustration that a targeted show may attract those patrons, but most of the time they don’t return for the next show or the next season.

In response, over and over, diverse patrons say they don’t attend full seasons of mainstream white theaters because they don’t see their stories being told consistently and don’t see people of color in leading roles consistently.

“Why am I going to go see The Taming of the Shrew when there’s nobody else that looks like me?” said Wade who contended he might go see Death of a Salesman if it starred local Black actor André Gainey.

It’s hard to feel comfortable and welcome “if you’re a Black couple going to see a white production in a white house and you are one of maybe seven other Blacks in (the auditorium). You already feel alienated,” Teddy Harrell said.

“Being made to feel welcome” does not simply mean loading up a season with “Black” plays, Harrell said. It’s a broader vibe that acknowledges differences from what is appropriate dress at a theater to audiences talking back to the characters on stage, he said.

“There’s a certain sector of the Black population that loves the arts and goes to theater,” Stephens said. “But then there are people who it’s not a part of their cultural experience….. Now, when they go in, they love it, so I think we have to find out what it is that keeps them out of the theater.”

Additionally, all audiences regardless of ethnicity over the past two decades have increasingly cherry-picked what they want to see in a specific theater’s season rather than subscribe. It’s a paradigm they apply in virtually every other entertainment option they patronize in the 21st Century from music to television to movies.

The onus of audience building among patrons of color solidly lies with the theaters, interviewees said. Cruz said in an interview with John Thomason last year for this website, “I think theaters need to not just program plays that are written by writers of different backgrounds, but they need to go into the communities—Hispanic and Black communities—and really try to invite those audiences to the theater because it isn’t just about presenting the work. People need to know that the work exists.”

Some theaters work hard at recruiting patrons of color with marketing programs when they believe the fare will attract that audience, such as the Maltz Jupiter Theatre did with The Wiz in 2015.

Still, some theater executives privately question whether that audience exists in significant numbers – or ever will — whatever the theater does.

Artists of color counter that the audience exists, but that they perceive the single title in a season to be, at best, perfunctory social consciousness, and, at worst, an intelligence-insulting pandering.

The current success of Miami New Drama is proof that a multicultural – even well-heeled — audience exists, said Hausmann and Richberg. Attendance at their theater benefits from Miami-Dade having a majority minority population. But the company has blossomed into a $4 million operating budget in four years and thrived because most of its productions are laser focused on speaking to its diverse community. Forty percent of the audience was African American attending its One Night In Miami drama about a true 1964 meeting of Malcolm X, Jim Brown, Sam Cooke and the boxer then known as Cassius Clay.

When the audience “sees themselves up there” on stage, a show can be an inarguable hit such as Garcia’s one-woman socially-charged comedy Fuacata! at Zoetic Stage depicting an array of Latinx women, a work co-written by Garcia and director Stuart Meltzer.

Plentiful Black audiences in New York paid top dollar last season to attend Christopher Demos-Brown’s American Son and Jeremy O. Harris’ Slave Play

And tens of thousands of African Americans from every corner of the country converge every other year on the National Black Theater Festival in Winston Salem, North Carolina, where more than 30 tragedies, musicals, comedies, movement pieces, and revues were produced in 12 venues by predominantly Black theater companies last year.

Of course, some theater leaders fear alienating their predominantly white core audience. “In order to change the mindset of the community, artists need to use the arts to make that change, but you can’t make that change unless the audience is willing to come and experience the change,” said Garcia.

But that is precisely where allegations are raised of systemic racism when white leaders program exclusively for white audience members and appear to only pander to audiences of color on occasion.

Furthermore, reluctance to altering the bulk of a company’s fare ignores that theater has never been a stagnant art form. It has continued to attract audiences as it has consistently but subtly evolved over two and half millennia. Current generations know it has been in metamorphosis over the past few decades with some loss in attendance due to competing art forms and entertainment choices.

The key may be to avoid surprising the audience with the evolution. It is the responsibility of the theaters as they make choices “to change and educate the mindset that comes to the theater,” Garcia said. “We know that there are communities that will not tolerate a Black man and a white woman on stage.” She asked rhetorically, “Is it our job to educate our audiences in tolerance, in compassion? It is our job to create programing that focuses on resetting that mindset, so in the future a Black man with a white woman would be commonplace.”

Company leaders believe it would be foolish if not suicidal to drop significant changes wholesale on the audiences without some advance warning, educating them what to expect and why changes are being made, artistic directors said. That extends from talkbacks to the careful crafting of publicity blurbs, Stabile said.

SPEAKING OUT; SPURRING CHANGE – WHOSE RESPONSIBILITY

“They can’t hear you if you don’t speak up.” –- Ron Hutchins.

Partisans disagree who should shoulder most or even all of the examination and reforms. In some cases, they believe their own group should be the prime player. Others contend the onus is another group’s responsibility. Still others argue that efforts will not be effective unless it’s a shared collaborative campaign.

On the national level, some artists of color have written that it’s not their responsibility to be the moving impetus in reform or to identify what problems exist for companies. They aver that the burden should fall on the companies.

“It seems to me like Black folks are always the ones who are looked on to solve the problem of race in America. Well, we didn’t create the problem of race in America. And I don’t see enough action on the part of white Americans to tackle the issue, whether it be artistically or socially or politically,” Stephens said.

Yet she and Hutchins strongly believe that they have a responsibility to call out the problems if there is any hope of solving them.

“I also think that if nobody’s ever called someone out on this stuff for what they’ve been doing… they need to be educated,” Stephens said. “Everybody’s so afraid of hurting somebody’s feelings or ruining their relationships. But you can have an intelligent conversation without it getting hostile and without putting people on the defensive.”

The hurdle, said several people like Alexander, is many artists do not want to get reputations as troublemakers in a profession where short rehearsal times pressure directors to hire people who are easy to get along with. Indeed, some artists contacted for this story balked to speak on the record.

To begin the change, some companies’ leaders are taking the challenge. They are voraciously reading the avalanche of online articles written by artists of color such as the bracing recent “We See You, White American Theatre” manifesto initially signed by 300 artists of color.

A few heads of theater companies are quietly meeting with artists of color, asking for guidance, or attending workshops on diversity and inclusion. Alexander has recommended multiple consultants in this region who can help identify deeply-entrenched but possibly unconscious practices and mindsets that need examination. She herself will lead a Zoom workshop on inclusion for the South Florida Theatre League on June 30.

But another group bears some responsibility going forward – those buying tickets and donating funds, interviewees said. Core audiences that spell theaters’ economic survival for the short run have to be willing to be open to uncompromisingly well-executed works and new-to-them voices that are not simply a reaffirmation of familiar fare and status quo. Similarly, potential audiences of color who say they don’t see their lives on stage have to put their money where their mouth is when theaters try to evolve in the long run.

And both have to give artistic directors feedback of their support of such moves – and financial support.

FUTURE SURVIVAL

“If we don’t open our eyes now, we will be left behind as an industry. – Nicholas Richberg

While a passion for social justice and a commitment to elevate the genre are sufficient reasons to pursue the challenges, another may simply be long-term survival.

In another decade or so, a significant portion of today’s core wealthy white audience will be dead or incapacitated. The ever growing percentage of “minorities” in this country, even in less urban areas, edges closer to aggregating into a majority of consumers U.S. Census data shows – something television advertisers began acknowledging a few years ago.

The theater community is “always asking, how do we make it relevant? Well, the fastest way to make it irrelevant is to make it a relic of a bygone era of a different demographic,” Richberg said.

Further, he continued, “if we’re going to inspire the next generation of artists, then it’s just a reality that the next generation of artists is not going to be as white as this generation of artists. And they’re going to have a different perspective. They’re going to have a broader view of the world.”

Hausmann added, “I profoundly believe that the next Great American Plays are going to come from communities diverse and multicultural as Miami.”

Lasting, meaningful change on so many fronts will take years to achieve and require a concerted effort akin to building a championship sports team, James Randolph reiterated.

But most people interviewed see this moment of upheaval and awareness as an opportunity, especially for Miami-Dade whose civic leaders see it as a harbinger of the multi-cultural society that the United States is certain to become.

“South Florida is so well positioned in a country with such a truly diverse populace that we really could be leading the way,” Richberg said.

Hausmann angered colleagues more than a year ago by accusing other theaters’ fare and leadership as not reflecting the community as his does.

A year later, he says, “And now the whole world is in the middle of a revolution… where people seem to be seeing a level of clarity that they don’t normally see. So maybe this is the time. I don’t want it to be wasted.”

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design

One Response to Racism & South Florida Theater: Changing The Dance Steps