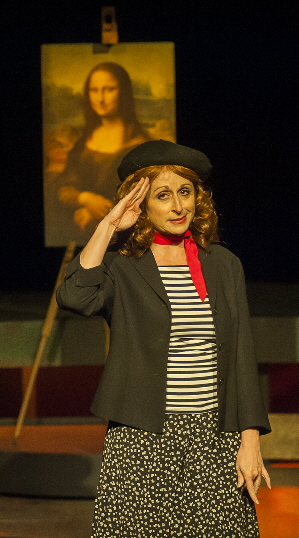

Paul Louis, Irene Adjan, Tom Wahl, Daniel Capote, Anna Lise Jensen, and Chaz Mena in Michael McKeever’s Finding Mona Lisa at Actors Playhouse/ Photos by George Schiavone

By Bill Hirschman

She sits center stage in a spotlight enigmatically smiling on a swirling array of people, events and eras. Her expression has not changed a millimeter – she’s a painting after all. Yet as a disparate parade of people describe what she means to them, something in her inscrutable mien changes as the audience sees the identical arrangement of oil on wood through their eyes.

The world premiere of Michael McKeever’s Finding Mona Lisa at Actors Playhouse initially might seem a light, fascinating beach read about Leonardo DaVinci’s masterpiece — a sometimes droll, sometimes broad comedy for a summer evening.

But much like the film The Red Violin, this episodic time-travelling romp is far more about the multi-faceted relationship of Art and human beings as La Gioconda seduces and mesmerizes people in different ways — from the psychotic who imagines a lover’s tempestuous relationship conversing with the painting to a bureaucrat solely concerned about the detailed logistics of transporting the work to America for an exhibition.

McKeever, one of the region’s most popular and talented playwrights, is well on his way to delivering an endearing insightful work here. The piece had a staged reading at Jan McArt’s series in 2012. But today’s play developmental process can takes two or three professional full productions to fine-tune such a promising work. This one, too, needs some more tinkering and tweaking before it can compete with McKeever’s best work such as Daniel’s Husband, After, Stuff or Clark Gable Slept Here.

It’s certainly entertaining as director David Arisco leads six actors in creating two dozen characters populating McKeever’s gallery through eight or so vignettes that spot the painting in various centuries and locales. They range from the court of French King Francois I to a 1911 New York City hotel room to Napoleon’s bedchamber. The scenes range from sex farce to social satire.

But while the wide range of tones and styles may be an intentional reflection of the variety of life, they don’t always mesh well together – especially since sometimes the tones shift disconcertingly within the same episode.

For instance, the last episode starts a sitcom skit with DaVinci in late middle-age being hectored by his father for not having a high-profile commission from the church or nobility. Michelangelo drops in to not-too-subtly brag about his Sistine Chapel project. Then arrives the Del Gioconda, the husband of the woman DaVinci has agreed to paint basically to pay the bills. All the men wear fake beards and wigs more likely found in a Saturday Night Live lampoon or Something Rotten. It’s likely meant to serve as a prosaic background to contrast for what is to follow.

Then the wife arrives, shyly reluctantly to sit for her portrait because she is not confident of her unconventional looks. The tone shifts markedly as the artist and his model gingerly make a connection and we see the eternal glory that is Art immortalizing beauty. It is a transcendent finale that has been undercut by the foolishness that happened earlier in the scene, as if everyone was afraid of presenting unalloyed sentiment.

Indeed, much of what is depicted humorously riffs off historical fact, but the most moving and effective piece (also shot through with gentle humor) is one McKeever seems to have invented from whole cloth.

Irene Adjan

Ellen (beautifully underplayed in a self-effacing way by Irene Adjan) is an outer borough denizen who was assigned a grade school essay about the painting when it came to Washington in 1962. Unable to see the actual work in person, she became obsessed with it throughout her life. As a housewife and mother, she and her dullard husband finally visit Paris to see the work, which they find, like everyone who sees it, is surprisingly small in physical dimensions. But what happens next to Ellen in a transformative stroll gifts her with a unique personal interpretation of the model’s quiet smile.

The pertinence of some scenes make sense thinking about them later and do as well on paper. But in performance, they don’t quite fit smoothly like the relevance of the protracted negotiations to transport the painting for that American appearance.

McKeever the writer does not indulge in verbal pyrotechnics to show off his skill unless it’s to whip off a bon mot. Instead, he writes in a smooth convincing vernacular that makes the heightened passions on display all the more believable because the characters speak as we do.

His plain well-crafted words sometimes deftly reach toward the deeper universal strivings of human beings seeking Beauty through Art. For instance, the madman says, “You know her. Her cool smile, her deceivingly gentle eyes. The strength – the cold feminine will—just there beneath the amber glow of her pale skin. Her utter lack of pretense. Unadorned. Clean. Quiet. Her outward appearance underplayed, as if to put focus on the beauty within. She’s clever that way. So clean . . . that beauty. So quiet. It hides so much. Just look at her, you’ll see. And then, you’ll understand.”

Or Ellen says of her first viewing in person, “There was something off-putting about it. Oh don’t get me wrong, she was beautiful. Truly beautiful. Even behind the two giant sheets of bullet-proof, triple-laminated, non-reflective glass. But there was something . . . something about her smile. When you actually see her in person, it’s different. Everything about her is different really. It’s like seeing a person in person as opposed to just seeing a photograph of them. Their features are all the same, but somehow they’re so much more to them. They literally come to life. She was like that. Seeing her in person is a little confusing . . . because you realize, for the first time, you don’t know why she’s smiling.”

But later, after an unexpected meeting with surprising results, she says, “And I stood there and looked at her. One last time. And suddenly, I got it. I finally understood the smile. It’s a smile that hides a secret. The type of secret that you fall back on when you’re feeling blue. The type of secret the mere memory of can change your entire day. The type of secret that makes you smile. I looked at this lovely woman trapped in this bullet-proof prison. For hundreds of years, people have ogled her and obsessed over her. Famous beyond words. Doomed because of it. Those simple, dark eyes have seen it all. I mean, she spent four years in Napoleon Bonaparte’s bedroom. The things she must have seen. And yet, through it all, she continues to smile that smile. No matter what. When I think of the secrets she must keep . . . So anyway, I went back to my life. Ebay and Harry and Dancing with the Stars. And there are still times I want to stick my head in the microwave. But, you know what? It’s all good. It’s all alright. Because now . . . I have a secret too.”

The cast nimbly shifts from personality to personality including Chaz Mena’s sexually rambunctious Napoleon trying to keep a mistress from being bothered by the portrait’s gaze, Paul Louis as an early French king unable to understand the idea of art being displayed for the public, Tom Wahl as the painter himself, Anna Lise Jensen in a gentle shaded portrait of the model herself and notably Daniel Capote (recently of Zoetic Stage’s The Caretaker and Island City Stage’s Perfect Arrangement) in a wide range of roles including the increasingly insane Bolivian who imagined relationship with the lady of the painting led him to throw a rock and damage the painting in 1956. But Adjan is the most impressive: Ellen one moment, a lecture hall scientist before that, later a jealous sister-in-law, and then a no-nonsense turn-of-the-century dowager.

If the production does not land as cleanly as it might, the evening glows with an alchemical magic in this quirky biography of a piece of wood daubed with oil that says more about the people observing it as it does about its model.

Full Disclosure: McKeever and I work as co-panel members on Iris Acker’s Spotlight on the Arts on BCON-TV.

Venting Rants: 1) Actors Playhouse is hardly alone in this sin, but its volunteer ushers regularly sit in the back and audibly talk through performances in the upstairs theater – yet rarely wander into the house to deal with people using phones. 2) Saturday night’s performance demonstrated why you should turn cellphones off, not just put them on silent: An Amber Alert or severe weather alert set off phones over and over and over and over and over and over a dozen times during the evening — and no one ever turned them off.

Finding Mona Lisa plays through Aug. 13 at the Actors’ Playhouse at the Miracle Theatre, 280 Miracle Mile, Coral Gables. Performances 8 p.m. Wednesday-Saturday, 3 p.m. Sunday, and 2 p.m. Wednesday only July 19. Running time 90 minutes with no intermission. Tickets $50-58. The theatre offers 10 percent off all weekday performances for seniors and $15 student rush tickets to any performance 15 minutes prior to curtain with identification. Discounts are based on availability. Visit actorsplayhouse.org or call (305) 441-4181.

A PaperStreet Web Design

A PaperStreet Web Design